Subli and the Journey of Transformation

May 5, 2020

“Oh, bless our God, you people! And make the voice of His praise to be heard…For You, O God, have tested us; You have refined us as silver is refined. You have brought us into the net;…We went through fire and through water; But You brought us out to rich fulfillment…I will pay you my vows, Which my lips have uttered…Come and hear, all you who fear God, And I will declare what He has done for my soul.”

Psalm 66:8-16, NKJV

In a moment of idleness, I surf through the internet, browsing through the thoughts of my acquaintances similarly isolated in space by the “Enhanced Community Quarantine” that has been imposed on the nation in the wake of the pandemic. A short documentary[1] pops into view on May 2, 2020, posted in a Facebook Messenger thread by a dear friend whose fascination with the Subli, the traditional Philippine devotion to the Mahal na Poong Santa Krus (Beloved Lord of the Holy Cross), a 4-century-old icon, rivals mine, although I am a Christian and she is not.

“Nagpaparamdam ang Mahal na Poon,” (The Lord is trying to make itself felt) I comment and push the “post” button in answer. Indeed, four times so far this terrible year, in the middle of my most hectic schedules in January and February, the subli diverted my attention and forced me to return to my early research routes in the 1980’s. The January 12, 2020 eruption of Taal Volcano, as the year was beginning, led equally old friends, the manunubli of Sinala, Bauan, Batangas to undertake a lakaran (journey of discovery) on January 15 to the mouth of the Taal caldera to appease the volcano, trailed by a camera crew from Rappler, which promptly posted a video report on the internet.[2] The quieting down of the volcano almost immediately after was attributed by its devotos to the miraculous power of the Cross. The video reached the attention of the Chancellor of my reputedly “godless” university, the University of the Philippines in Diliman. His special events team at the Diliman Information Office contacted me to ask how they could get in touch with the Sinala group to perform a thanksgiving as part of an elaborate ceremony marking the end of his 6-year term held on February 21.[3] The joyous reunion at the University Theater between me and the Sinala troupe was one of the highlights of that month for me. Then came Covid-19, the lockdown and my hospitalization. I was engrossed in refocusing myself and getting used to the “new normal” when on April 29, a young facebook friend from Batangas City that I barely know posted a stunning performance of the Agoncillo version of the dance by a Batangas high school troupe in honor of International Dance Day.[4] The video struck a resonant chord in me but I tucked it away, busy with my writing, and playing the piano, and organizing a series of virtual videos with a group of enthusiastic young choristers. And then, on May 2, a final tug at my consciousness, posted a day before the annual Feast of the Holy Cross set me to thinking, “Yes, I have nearly forgotten to include, in my reflections about the intersections between music and faith, the long and complicated journey I have taken with the subli and the strange paths it has led me through.”

I recalled how I had persistently tracked down the subli in the 1980’s, after reading an entry in the card catalogue of the then Department of Music Research listing it as a musical form found in the hillside village of Luklok, Bauan in Batangas, the ancestral home of my husband’s family. I remembered how I had pestered my mother-in-law, until she introduced me to an elder/uncle in the neighboring community. I remembered my first encounter, courtesy of Manong Ehel (Gil) Caringal, with five manunubli from the village who performed for me in the front yard of our family home in December of 1980. The dancers came to my mind’s eye – Nicasia Mendoza floating effortlessly through the space, as her fingers performed the dainty gestures of the talik; and her brother Donato displaying the forceful patumbak (stances reminiscent of kali, the traditional martial art of the region). The pair performed to the accompaniment of an incredible tugtugan, a 3-footed drum carved in 1911 (the year of another great eruption of the volcano) out of a large piece of langka wood covered with bayawak (monitor lizard) skin. There and then, I made a panata[5] to focus my research life on this compelling devotion.

Immediately, I discovered that there were songs being sung. They were almost drowned out by the visual display of the dance and by the persistent drone of the drum, but they were there. Obsessed, I arranged for interviews with the leaders (matremayo) through whom the ancient lore had been transmitted. In the course of my archival research, I was to realize that the dance and its songs extended all the way back to the early 17th century, the first decades of evangelization of the Philippines by the Roman Catholic Church.[6]

Together, in the patio of my home, a small group of manunubli and I undertook to render in written form the full text of the subli songs they had learned in their youth. At the end of the session, Ate Eufemia “Piming” Caringal, patted my knee and said to me, fondly, “Agay, naibigay ko na sa iyo lahat ng kaalaman ko.” (Child, I have given you everything I know.) Minutes later, she collapsed in front of me, stricken by a massive heart attack. We rushed her to a nearby hospital, where she was pronounced dead on arrival. Her brother, Buenaventura “Manong Tura” Caringal was to tell me later that his greatest wish was to die singing and dancing the ancient awit, as she had.

Recovering from the trauma, I wrestled with the song texts and their archaic language and dense, sometimes unfathomable talinghaga. I wound up interviewing the remaining manunubli; scouring old Tagalog vocabularies and dictionaries for ancient terms and idiomatic expressions from 1611,[7] 1703,[8] 1754,[9] 1914;[10] searching through old books about Philippine medicinal plants and their properties;[11] learning the basics of Spanish paleography to decipher handwriting in early colonial manuscripts. Slowly, the vision of the dawning of that early Christian world in the Philippines began to emerge.

The traditional figurative language of the subli texts, as rendered in dense and sometimes even opaque imagery, is called talinghaga. It is difficult for the contemporary reader to fathom. But as I began to decipher the secrets of the archaic Tagalog, transmitted orally to contemporary singers who may not have understood many of the terms they sang from memory in their childhood, the narrative of the subli came into view. The text records the journey of the first manunubli from the town of Bauan in the 17th century, in search of the cross that had been making miracles in the escarpment called Dingin on the shore of Lake Bombon, now called Lake Taal.

The song texts may be divided into two sections. The first fifty-seven (57) verses narrate a journey in space and time to search for the cross – the mustering of the company of spiritual adepts from Bauan, the difficult, dangerous lakaran that follows, the arrival at Dingin, the enthronement of the cross, the struggle of the Bauan manunubli with groups from two other towns (Lipa, Tanauan) for its possession and the transformation of the natural world as a consequence of the appearance of the icon. This section is sung with neither dance nor drum accompaniment.

The second section, which consists of one hundred and one (101) stanzas, is a set of dance songs of praise and adoration in celebration of the Holy Cross, featuring elaborate floor patterns with picturesque names sung to the accompaniment of the tugtugan - Pitong Kahoy, Santa Krus de Mayo, Mababangong Rosas, Binilin-Bilin, Pilit, Pupol, Salta, Garambola, Balagbag, Bilao, Paalam. Later, from the neighboring town of Agoncillo, I was to discover even more songs – Maliwanag, Heli-Helina (Hali-halina), Kanta Lalo Na.

The excellence of the talinghaga makes the poetry both beautiful and deep. The spiritual character of the company assembled at the beginning of the text is made evident by the terms they use to refer to each other – “kambulong” (co-whisperers of spells and incantations), “kapipino” (refined ones), “katampok ng singsing” (fellow ring-stones/gemstones/talismans), “damoro”(healing herbs and spices) and “kabulaklak” (fellow flowers, which are part of the ritual paraphernalia of praise and worship). The cross that they seek is referred to as a “hagdang pagpalangit” (staircase to heaven), a “timbulan” (buoy) to cling to when drowning, a “baras” (straight rod), a “tungkod” (cane, staff or support), a “gamut” (healing agent), a “silungan” (shelter), a “sula” (radiant red gem), a “mayabong kahoy” (flowering tree with luxuriant growth), a “Krus na berde”[12] (Cross of the lost).

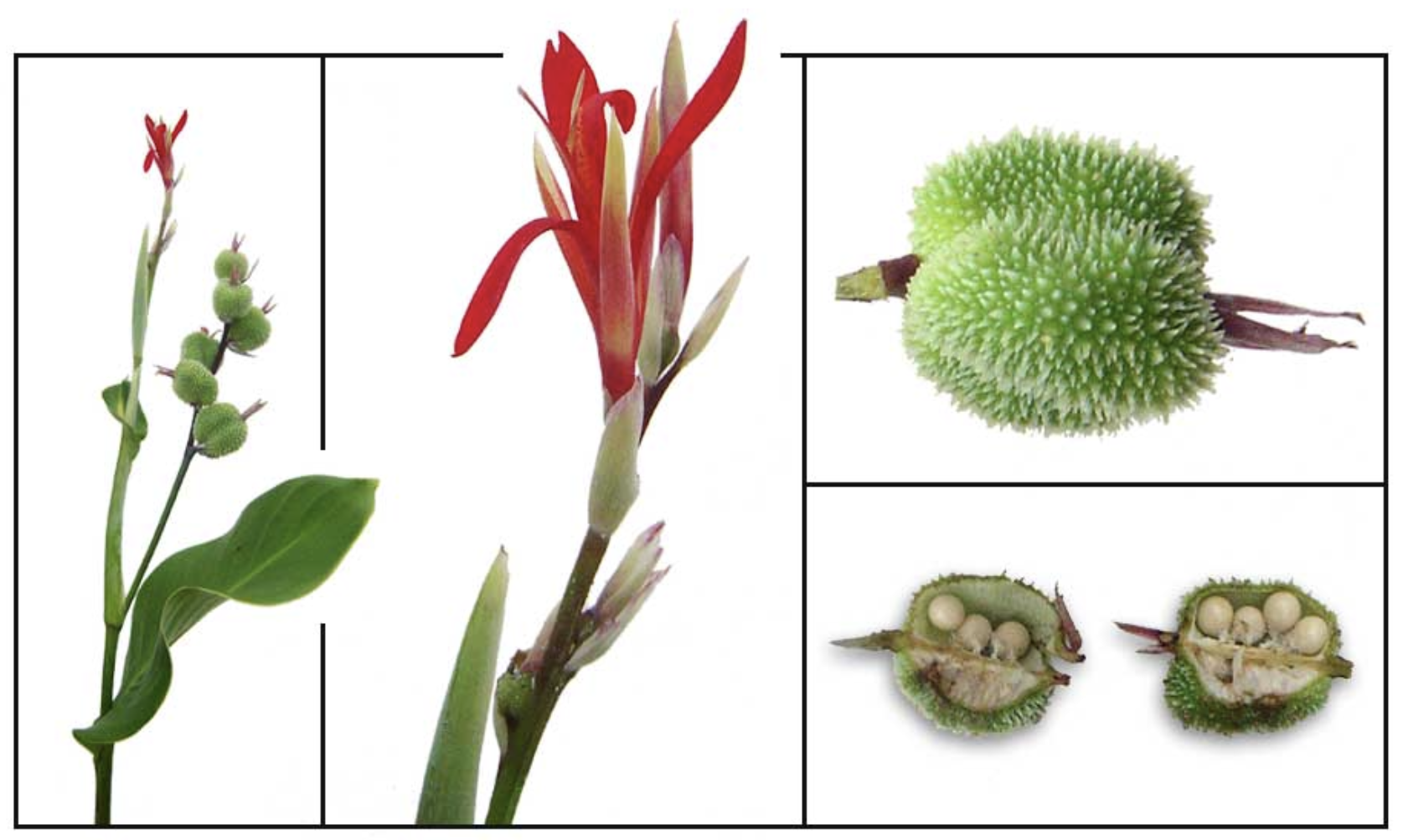

For me, the imagery most difficult to fathom came from four stanzas (54-57) that deal with the transforming power of the Mahal na Poon. The texts are peppered with ancient plant names - timbo, lagolo, tikas, bayabas, pisig, talahib, paite, lagundi – all with healing properties.

Unravelling the effect of each plant in the parallel series of verses was also a struggle since the botanists of the 1980’s were only beginning to realize that ethnobotany was an important source of medical knowledge and as a result, were neither familiar with the old plant names nor their medicinal properties. An example comes from verse 55:

Sa una’y ang tikas

Ang dahon ay bayabas

Ngayo’y kaibangibang hinap

Ang tumubo’y perlas.

In the beginning, the tikas

Leaves were like the guava’s

Now, they have a different shape

And pearls have sprouted from them.

Ticas-ticas.

Ticas-ticas rosary.

There leaves of the tikas-tikas plant, were once boiled in water and used as a diuretic preparation; just as the bayabas, or guava leaf is considered a basic medicine among the Tagalog people. But with the arrival of Christianity, this use of the plant was forgotten, except among herbolarios (practitioners of traditional healing) and their likes. At the same time, the waxy beads found inside the sacs on the underside of each of its flowers were fashioned into rosaries used in Catholic prayers. In the verses, plant after plant is transformed, disappearing from view as part of the traditional healer’s arsenal of curative preparations and reappearing as an object in the Christian complex of worship. Cinching my reading of these verses was another one, found in all three Luklok, Sinala and Agoncillo versions, with an identical poetic structure, but authoritatively stating:

Sa una’y ang kasaysayan

Bundok at kaparangan

Ngayo’y naging simbahan

At mapaglulubinasan.

In the beginning, meaning

(Resided in) the mountains and valleys

Now it is in the church

And novenas (are performed there). (my translation)

Taal/Bombon.

Well of Sta. Lucia, Casaysay, Taal.

My notes for this passage from 1989 read:

The locus of spiritual power has shifted from the mountains and fields to the church. The term, simbahan, as used in old Bauan is best translated as “place of worship.” Pre-Christian rituals are said to have been celebrated in caves and mountains. Even today, certain caves and cavelike natural formations such as Dingin, are referred to by local residents as simbahan. However, the text describes the simbahan in question as having a “pintong may balantok,” or door with arches…Thus the simbahan in question is no longer a natural, but a man-made place of worship, probably the church of Timbo. The transfer of the Mahal na Poon from Dingin to the Church of Bauan in Timbo is symbolic of a critical moment in our religious history.

In the light of my daily habit of Bible study at dawn, I revisit the richly textured verses and the soaring metaphors of faith. Immediately, Psalm 66 and the Psalm series 120-130, commonly referred to as the songs of ascent, songs sung by pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem, the Holy Mountain of Israel, fill my conscious thoughts. In my mind’s eye, I imagine this band of ancient healers, going off in search of the newly found cross, travelling through the dangerous terrain of the volcano, singing songs on their way, and dancing for joy as they approach the holy icon and seek its favor. For the language of the subli is the poetry of the phenomenon of metamorphosis. In their adoration of the cross lies a figurative speech that solidifies this transformation of the universe into a Christian one. Bodies of sky, land and water; creatures on earth, birds and other animals; trees, plants and flowers change before the eyes of these 17th century travellers through the spaces we now populate as they let go of the old familiar world and bravely embrace a brave new one.

In so doing, I retrace my own spiritual journey – through an early decision to serve as choir director in the familiar music ministry of my then local church; through the Lord’s rejection of this offering of myself in His service; to the almost simultaneous offer of a research grant from a national agency to document the subli; to my timorous acceptance of the challenge and the subsequent struggle to fulfill all the expectations that confronted me in the field. There were the strenuous physical efforts to reach my informants in hillside villages - the sinking into muddy paths, the sliding and falling into streams, the slipping on rocky climbing trails and the resulting permanent injury to my spine and my back. There were the challenges to a city girl born and bred in the intellectual atmosphere of academe to “fit in” to the conservative rhythm and spirit of their very traditional farming and fishing communities. There were the dangers of bringing the research into the public eye – the maneuvering through bureaucratic and institutional intrigue; the slipping through historical events, political upheavals and military coups to bring this experience to book launches, festivals, academic conferences. And always, always, the fear that people of my own faith community, rooted in an American interpretation of Christianity that has dominated our religious sensibilities since the second half of the 20th century, would judge me and question my work as propagation of an earlier, still persistent Filipino response to the faith that we thought had lost its validity in modernity.

But the Lord has always been there, both to test and uphold me in this project. He has pushed me to excavate the evidence of the past, has allowed me to see how it operates in the present and perhaps has led me to understand how it might shape the future. By doing so, He has stretched me to the point of breaking, but the spiritual rewards have been unimaginable. The journey has transformed me as well. And so, as the ancient manunubli of Bauan, Batangas sang, so do I:

Santa Krus de Mayo

Bandila ka ni Kristo

Ay kami’y prapyuhan mo

Ng mabangong amoy mo

Mahal na iyong samyo.

Holy Cross of May

Banner of Christ

Bestow on us

The rich scent of

Your fragrance.

[1] Invencion de la Sta. Cruz Parish, Alitagtag, Batangas. “Salubong sa Mahal na Poon na Santa Krus,” videodocumentary posted on Facebook, May 2, 2020.

[2] Rappler “Dance as Prayer,” posted on Facebook, January 15, 2020.

[3] “Paglinang at Pagbunga,” Opening Convocation for Diliman Week, February 21, 2020

[4] PJ Medrano Caringal, Likhang Sining Dance Company of the Marian Learning Center and Science High School, posted on Facebook, April 29, 2020.

[5] Elena Rivera Mirano (et. al) Subli:One Dance in Four Voices/Subli: Isang Sayaw sa Apat na Tinig(1989). The term panata is translated loosely in English as “vow.” Among the Tagalogs, it is better defined as a practice of forging a relationship with Deity and the process of fulfilling this relationship.

[6] Pedro de San Buenaventura, 1611.

[7] Ibid.

[8] De los Santos

[9] Noceda and Sanlucar

[10] Pedro Serrano-Laktaw

[11] Blanco, Merrill

[12] The term “berde”, in this sense, as derived from the Spanish “perder” or "to lose." The word is associated with cockfighting, where “naberde” refers to a wager where one loses everying. The cross, in this sense, may not only be possessed by the winner but also by the losers, the lowliest of the low.

Elena Rivera Mirano, et al. Subli: One Dance in Four Voices/Subli: Isang Sayaw sa Apat na Tinig, Cultural Center of the Philippines, 1989.

Invencion de la Sta. Cruz Parish, Alitagtag, Batangas. “Salubong sa Mahal na Poon na Santa Krus,” videodocumentary posted on Facebook, May 2, 2020.

PJ Medrano Caringal, Likhang Sining Dance Company of the Marian Learning Center and Science High School, posted on Facebook, April 29, 2020

Rappler “Dance as Prayer,” posted on Facebook, January 15, 2020.